By Mohammad Reza Heidari

Critical thinking is one of those skills that can shape individuals’ identities. Having a discerning perspective on the content we consume throughout the day and recognizing its strengths and weaknesses can help us develop our own unique tastes and separate ourselves from those who blindly follow anything. However, Red Dead Redemption 2 is exactly the kind of title where critical thinking shouldn’t be present to enjoy it.

In essence, criticizing is not only the right but also the most important duty of the audience; so when a work demands its audience to refrain from thinking critically about its flaws, it’s not far-fetched to imagine that we’re facing a severely weak title that can’t even justify its own problems.

In this regard, RDR2 is one of those exceptions that, not to conceal its weaknesses, but to ensure that the audience can enjoy it to the fullest, asks this of them. From the very beginning and with ample suspension in its atmosphere, Red Dead Redemption 2 tells its audience, “Please trust me from now on.” This trust ultimately transforms the game into the pinnacle of storytelling and character portrayal in the history of video games, rather than just a tedious horseback riding simulator with nothing new to offer.

Before talking about this trust, thinking, storytelling, and character development, we must become acquainted with the double-edged sword of RDR2, which lies at its core. The crucial question to ask oneself in understanding this element is: What is the biggest strength of Red Dead Redemption 2 for you? Some may consider the story and its characters to be its finest aspect. Others might argue that it’s the game world that distinguishes it from other titles. And perhaps some view not a specific component but the collective of these elements as the game’s strength.

Now, if we were to delve a bit deeper into the question, it could be said that RDR2 owes its success more than anything to the cinematic experience it offers to the audience. An experience that, while transforming this work into an unforgettable masterpiece, forces the creators to accept a significant risk: deviating from its identity as a video game.

But before delving into the essence of the matter and understanding how Red Dead Redemption 2 exactly attains such a position, we must first dissect and set aside all its constituent elements to ultimately reach the core of the game and have a look at its golden heart.

This article is not intended to be a comprehensive critique of Red Dead Redemption 2; however, nonetheless, there are abundant spoilers ahead that it’s definitely better to avoid confronting them before experiencing the game fully.

The death of open-world due to linear levels

Perhaps the term “negative synergy” has caught your attention. Negative synergy refers to a situation where two elements individually have more benefits than their combination. This is exactly the state in which the overall design of RDR2’s gameplay resides; two completely contrasting and separate elements are present with maximum intensity, which are not seen together in any other Rockstar games.

RDR2 is Rockstar’s best open-world. After years, finally, one can spend hours in their game world and always have something to do. It’s enough to have a little interest in horseback riding in the wild west or exploring the burgeoning cities to spend dozens of hours wandering in that world.

But it’s precisely during one of these free wanderings that you arrive at the Van der Linde camp and one of the main missions of the game. Right here, the game throws away its entire world and becomes such a linear experience that you even need permission to walk around. The level design itself is so severely limited and restrictive that Red Dead Redemption 2’s gameplay needs a separate article, and for now, we overlook them and only consider the strength of this style of level design, namely its incredibly powerful storytelling ability, as intended by the developer.

In fact, the contrast between these limited and highly linear cinematic stages and the open and unlimited world of RDR2 ultimately leads to the emergence of negative synergy in its gameplay structure. Arthur Morgan can spend days away from camp hunting and fishing, causing chaos in the game’s cities, and the game world never tells you that you can’t do something you want to do.

The biggest narrative problem arises when instead of enjoying the sandbox of the game, you enter levels that don’t allow you any practical freedom. Throughout the entire game, it’s only during these narrative levels that the game reminds you that Dutch and his gang are wanted criminals and acts against them. Nowhere in the game does it say that the longer you delay Dutch, the more likely it is for everyone you know to die; however, as you progress through the story of Red Dead Redemption 2, the threat of the Pinkertons and their threats to the group becomes more serious, and the game unsuccessfully tries to show time for the group to escape the tight noose.

And here is where RDR2 for the first time asks its audience not to think. The game directly asks you to forget about the existence of Pinkertons when you’re in nature and when you reach narrative stages, forget that this game is a vast open world. Perhaps initially, the writers somewhat tried to cover these gaps, but from the second half of the game, there is practically no attempt to link the open-world and narrative aspects of RDR2, and it’s only by closing our eyes to all these flaws that we can have an enjoyable gaming experience.

Contradiction will arise

Perhaps one of the definitions (or criticisms) that can be abundantly seen about Red Dead Redemption 2 is its very close resemblance to a modern western film. Regardless of whether this feature is good or bad, RDR2 throughout its entirety tries its hardest to have a narrative reminiscent of a reflective western film.

Again, it’s right here that another strength of RDR2 and the difference in its essence from the previous version lead to the emergence of some unavoidable problems in the game’s structure. Revisionist western is a relatively new subgenre of the western style, which aims to provide a realistic identity to this genre and has almost been forgotten. Unlike spaghetti westerns – the genre in which RDR1 falls – revisionist western removes the romantic elements of old western stories (hero, love, evil villain character, etc.) from its story to confront us with gray and realistically suffering characters facing the wild west of their time.

Red Dead Redemption 2 also, as it should, turns its characters into deeply layered individuals who are not seeking to save the world or achieve eternal love. In this revisionist western, we are on the side of the fallen villains whom lawmen are after, and from the beginning, we are sure they’ve reached the end of their journey.

However, the game with its open world practically allows the audience to eradicate this realistic theme and engage in bizarre and unrealistic activities. Although this freedom inherently questions the entire theme of the revisionist western aspect of the game, the creators cannot be blamed for what the audience does; rather, the creators and writers of RDR2 make a mistake when they incorporate these elements into their main storyline.

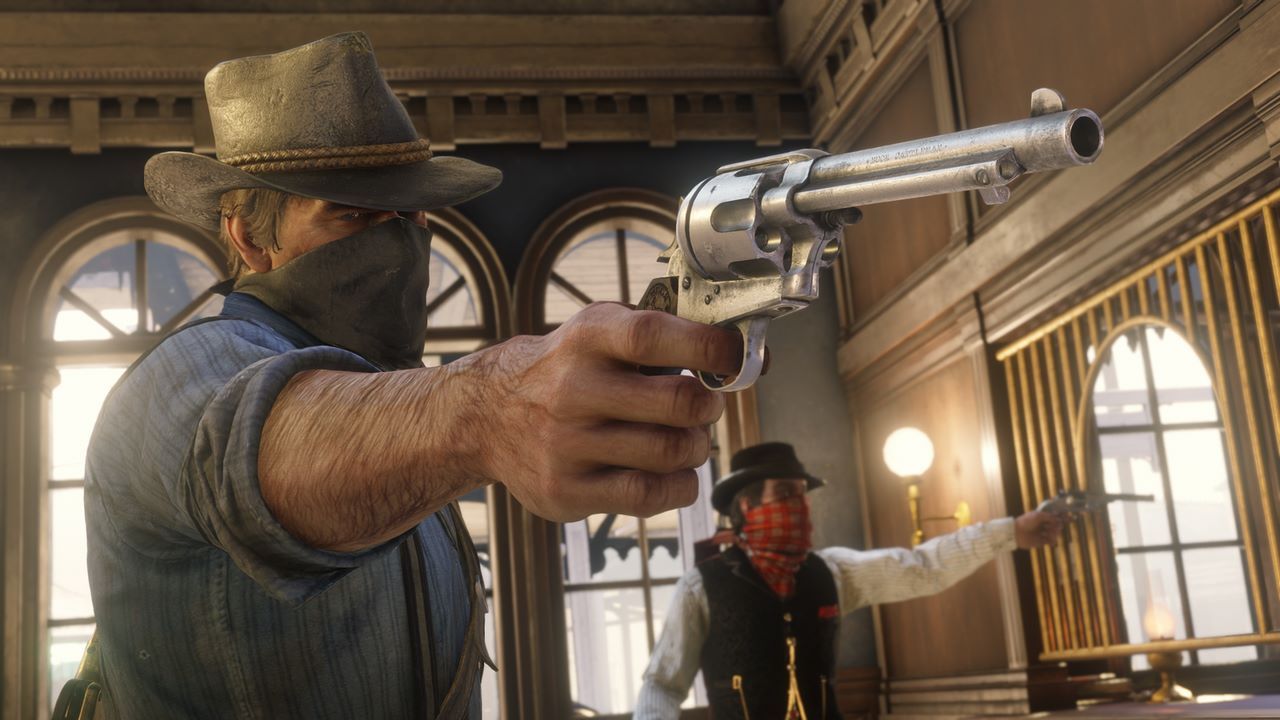

Let’s fully understand this issue with an example. In one of the final stages of the game, Arthur and Dutch, who have almost nothing left, attack a train. In part of this stage, Arthur takes control of a machine gun and starts killing soldiers who are responsible for guarding the train. Right here, two fundamental problems arise in the game’s structure:

Firstly, contrary to the realistic theme of the story, Arthur easily starts killing dozens of trained soldiers, and not even one of the remaining gang members are killed during this robbery, with only one of them going to prison. This stage is one of those moments where RDR2 abandons its identity as a realistic story and asks its audience to not think about the things they see and be satisfied with Call of Duty-like stages.

The second problem, however, is something that almost enters the game’s story for the first time. During this part of the game, we witness a very clear example of ludonarrative dissonance. Arthur Morgan, who until recently was talking to a nun about fear of death and passing by a widow’s debt, now without any penalty from the gameplay, starts killing dozens of innocent soldiers.

Actually, how do we know that one of these soldiers isn’t afflicted with the same illness as Arthur? How do we know that one of them isn’t the same age as Arthur’s former sweetheart’s brother? How do we know that another woman isn’t supposed to become a widow if one of these soldiers is killed? The game simply disregards all of these questions to briefly turn into a pure blockbuster third-person shooter.

Such stages throughout the lengthy campaign of Red Dead Redemption 2 are by no means scarce, and the game not only abandons its main identity in these stages, but also asks its audience to stop thinking and “feel” the life of Arthur Morgan, a gunslinger.

For the Sake of a Handful of Choices

Having the right to choose in video games not only allows the audience to have a greater sense of connection with the work but also enhances its replay value by covering certain parts of the game. RDR2’s choices are by no means like this. In Red Dead Redemption 2, you have two different choice systems: inconsequential choices and the honor system.

Inconsequential choices, as the name implies, are minor and inconsequential choices! Throughout the game stages, without any reason or systematic order, two or three very minor and meaningless choices are presented to you, and the game practically asks you to step out of its cinematic experience for a few moments to decide whether your character goes first or follows.

The initial two or three choices in the game give players who have previously experienced choice in other titles the impression that these choices will affect the characters’ destinies personally or at least change the mission’s course. The reality is that in RDR2, the player will understand not by seeing the futility of their choices, but by realizing the small impact of these choices – and then, seeing the futility of their choices – that there is no reason for these choices to exist in the game, and their only function is to eliminate the sense of immersion in the game world and replace it with that of the main character.

On the other hand, we have the honor system (read: salvation system), which differs from all the elements we’ve discussed so far. The honor system in Red Dead Redemption 2 not only undermines the sense of narrative realism that the game consistently strives to convey but also negatively impacts the gameplay and the enjoyment of many players solely due to its significance.

In fact, a player who chooses to refrain from engaging in the dynamic sandbox of Rockstar and prefers to have a noble Arthur Morgan, who doesn’t partake in massacres in the game’s cities or rob trains, still risks losing part of their honor by accidentally colliding with someone on horseback; simply pressing the wrong button can diminish their honor unintentionally; they might have choices that are morally justified according to their own standards but the game deems them wrong (for example, saving a horse from being tortured by shooting it with a bullet still diminishes your honor).

This is while the game forgets to give importance to the honor system throughout its stages. Arthur’s and his friends’ honor isn’t diminished by robbing a bank and slaughtering police officers, or even during the train robbery stage, killing soldiers has no effect on Arthur’s honor.

And these flaws only exist for those who are unaware of how manipulable and unrealistic this system is, as it only takes one day of returning fish to the river to maximize your honor. Can massacring a town be compensated for by greeting the people of another town? According to the logic of this system, yes! Can chopping wood for the camp captain atone for a lifetime of criminal behavior? Again, yes!

The only way to rid yourself of such a system is to disregard it entirely and live as Arthur Morgan, playing the role you choose. Playing as a noble Arthur Morgan or a wicked outlaw is entirely up to you, and even though you don’t see the consequences of your choices story-wise until the end of the game, it still rewards you based on your playstyle.

Simply put aside this system altogether and only resort to it when necessary (which is highly unlikely since the final stages of the game easily raise your honor). Here, the game once again tells players to close their eyes to another aspect of its structure and continue to trust the game to provide an unforgettable experience in the end.

There’s no room for thinking

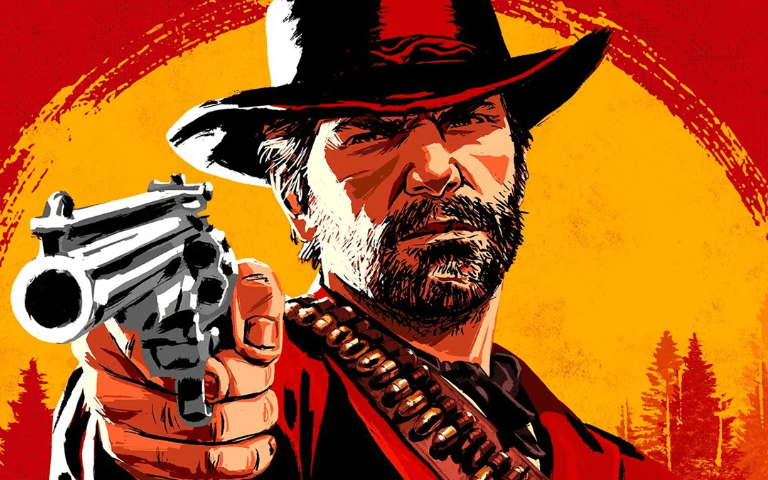

It’s logical to conclude at the end of such an article that RDR2 is a disappointing title with unforgivable flaws. My response, and probably anyone else’s who has delved into this title, is this: That’s not the case. Red Dead Redemption 2 actually begins when you stop thinking of it as just a video game; when you finally feel the dynamism of the world Rockstar has painstakingly crafted over the years and start living in this world like an anonymous gunslinger in the wild west.

For many people, RDR2 is remembered not for its tragic story, but for Arthur Morgan’s camping trips in the heart of untouched nature. For many others, these linear stages are not what ultimately stick in their minds; it’s the story and multi-layered, deep characters of the game that remain in their memories for years, because Red Dead Redemption 2 is a title that, if trusted, engulfs you. Rockstar’s magic lies not in innovation in structure, but in the juxtaposition of elements that together create an emotional experience for the audience.

The game’s maximum effort is to give you the feeling of watching a cinematic film. The graphic style of the game is not photorealistic but rather resembles a painting, drawn as close to reality as possible while still embracing its painterly quality, using its canvas to create dramatic scenes. The world-building and atmosphere of the game are vivid throughout, and alongside all this, the exceptional sound design and unforgettable music contribute to placing RDR2 on a list of titles that shouldn’t be thought about, but rather felt.

The art of Red Dead Redemption 2 and its duality lie precisely in making you accept, without realizing it, that you’re not just enjoying watching a film, and what you’re staring at on your monitor isn’t just another video game. The entire purpose of this game is to seamlessly transform from a video game into an indistinguishable reality, and it easily achieves its goal because it knows that its audience trusts the experience it has crafted for them.

In essence, Red Dead Redemption 2 exemplifies the famous Lombardian phrase: “Perfection is unattainable, but if we chase perfection, we can catch excellence.”

Comments